Climate change, housing supply, and The Economist’s grasp of economics

In the current issue of The Economist, an article on the impact of climate change on residential property has gained a lot of attention. Home ownership is a prevailing interest for the vast majority of middle- and upper-class people around the world, who often hold a large percentage of their accumulated wealth in the form of land, bricks and mortar. I’ve lived for extended periods in Sydney, Philadelphia, and London, and if there’s anything that raises the hackles of suburbanites it’s the current market value of a renovated three-bedroom with decent transport connections.

The Economist article actually does a good job of describing the game of insurance pass-the-parcel that is likely to play out as the climate continues to warm, and I’ll discuss this in my next article. However, the first part describes – very selectively – the possible effect of climate change on property values, which is my primary focus here.

Before I get into my critique, I’ll first note that you probably don’t read Unpacking Climate Risk because we parrot the views of other people. We’ll always try to offer a critical eye and keep fawning reverence to an absolute minimum.

The authors state that “10% of the world’s residential property by value is under threat from global warming” and that “climate change and the fight against it could wipe out 9% of the value of housing by 2050 – which amounts to $25trn.” They then go on to describe the apparent paradox of the run-up in Miami house prices over the past decade despite major concerns about the long-term habitability of the region.

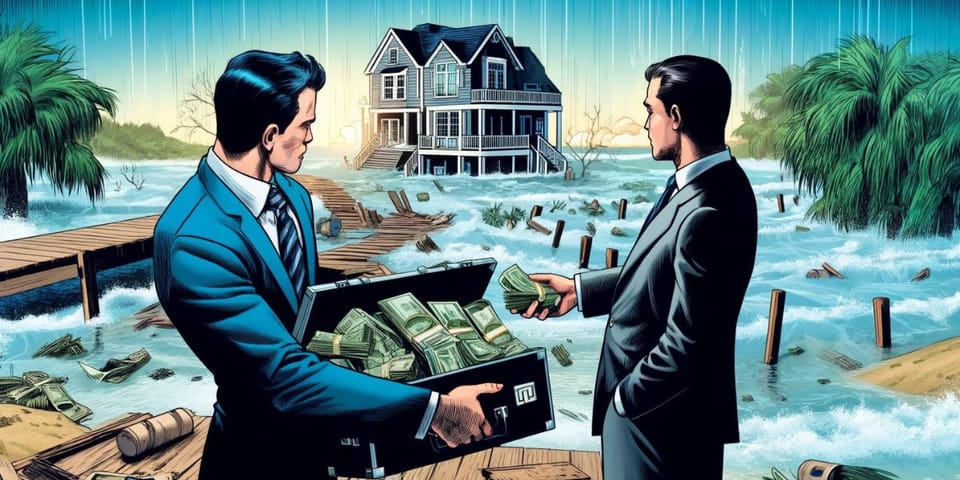

I find it genuinely troubling that The Economist, of all publications, has forgotten about the laws of supply and demand. When a house is destroyed by climate change, which appears to be imminent in the picture that accompanies the article, there’s no suggestion, except in tragic circumstances, that the lives of the occupants will also be lost. They will continue to work to earn income and they will still demand, among other things, shelter from the more frequent storms. The destruction of the house represents a clear supply shock but demand for housing will be largely unaffected.