Climate risk management according to Louie

Let’s clarify a few things from the get-go. I’m not a risk manager at a large financial institution. Nor am I a climate scientist. I’m a writer.

Yes, I’m a writer who’s been immersed in the world of climate-related financial risk management for half a decade now, but still. Some may want to discount my philosophy of climate risk management on the basis of my practical inexperience – and that’s fine. Hopefully it still makes for good reading.

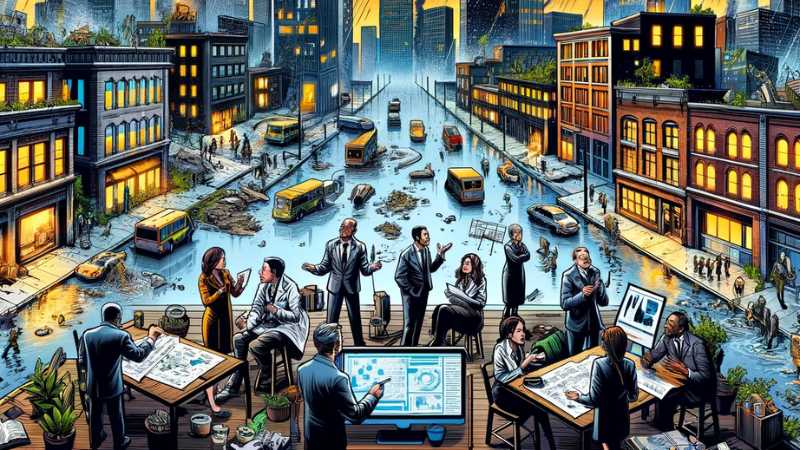

I believe the anthropocene is made up of a highly unstable network of systems: climatic, environmental, economic, financial – the list goes on. This instability isn’t inherently “good” or “bad”; it just is. However, it does mean that the past is a poor guide to the future, and that an approach to climate risk management that lacks imagination, inventiveness, and flexibility is doomed to failure.

This is nothing you couldn’t glean from the fine print disclaimer for that hot new investment product you’ve seen advertised. Still, it’s worth internalizing what it means. Ultimately, it’s saying there are limits to empiricism. In other words, historical experience is not enough to go on when it comes to estimating how climate change will impact the future. In turn, this means that approaches to climate risk management that rely solely on historical data are going to do a shoddy job preparing financial institutions – and the world at large – for what’s ahead. As climate change progresses, the anthropocene’s underlying systems will destabilize with increasing violence and unpredictability, making what came before an ever more unreliable guide to what’s to come.

This doesn’t have to mean that gut feelings and unfounded assertions are all we’ve got to go on. Forward-looking climate models have a pretty good track record when it comes to tracking the correlation of greenhouse gas emissions and temperature increases (“so far”, being a very important qualifier here). The laws of physics and thermodynamics are robust, after all.

The relationship between global warming and certain physical impacts is also fairly simple to extrapolate. The conclusion of the world’s scientific community in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report is that for every 0.5°C of global warming, there are “clearly discernible increases in the intensity and frequency of hot extremes, including heatwaves (very likely), and heavy precipitation (high confidence), as well as agricultural and ecological droughts in some regions (high confidence).” We can use these to guess at the frequency and severity of climate-related physical risks over time.

Of course, what’s far murkier is how the relationship between these risks and human systems will change as warming increases. Up to now (1.48°C above pre-industrial levels) it’s possible to argue that climate risks have not had a systemic impact on global economic and financial systems – though the role the public sector has played in maintaining a facsimile of business-as-usual should not be ignored. However, predicting how these systems will respond to escalating climate hazards beyond 1.5°C of warming, requires a healthy dose of speculation. After all, there’s a reason why 1.5°C is the limit enshrined in the Paris Agreement. It’s one of those thresholds beyond which things are likely to get truly weird, terrifyingly so from a risk management perspective.

This explains the financial industry’s preoccupation with forward-looking climate scenarios, which are being deployed by central banks, supervisors, and financial institutions themselves to try and identify the scope and scale of climate-related risks. How useful scenario analysis is for this purpose is hotly debated, as are what approach(es) are most effective. At their best, scenarios can map the linkages between (potential) climate risks and (potential) financial impacts, as well as the “transmission channels” that connect them. At their worst, they can produce fantastical depictions of the future where the impacts of climate change are either impossibly vast, or infeasibly slight.

There’s an argument to be made that when you strip away the pretense, scenarios are just educated opinions on the future. This doesn’t disqualify them from the climate risk management toolset. Another phrase for “educated opinion” is “expert judgment”, and modern risk management is dependent upon it.

When you get down to brass tacks, the interest rate decisions of central banks are little more than aggregations of expert judgment applied to data. The amount of loan-loss reserves banks put aside against dubious loans, too, are informed by expert judgment. Even the quantity of collateral a dealer demands to backstop a derivatives portfolio depends on the same. Indeed, there’s no facet of risk management that expert judgment isn’t applied to at one point or another.

Why shouldn’t this be the case with climate risk? When it comes to economic and financial system responses to climate change, we are ultimately talking about human behavior, which all too often defies the meticulously designed models of economists and risk managers. In this context, expert judgment – informed by useful data where available and rigorously challenged by credible authorities whenever possible – may be the more decision-useful tool.

I agree it’s an uncomfortable notion, admitting that the empirical approach can only take us so far. The Bank for International Settlements goes so far as to identify this as an “epistemological obstacle” to effective climate risk management. Put simply, intellectual habits that were healthy under certain circumstances are becoming increasingly problematic when addressing climate issues. What’s needed is an “epistemological break” in the financial sector that unshackles risk managers from inherently limited historical data and forces them to confront the radical volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity of climate risk.

If this makes old school risk managers uncomfortable, that’s precisely the point. If the anthropocene is entering a new phase, and the science says it is, then it stands to reason that risk management methods forged in the obsolescing phase will not be fit for purpose. Of course, some of the new approaches being tried may fail the test, too. That’s not a reason to dismiss them all as voodoo and doom mongering.

We need to get comfortable being uncomfortable. It may be the only way to truly prepare ourselves for the trials to come.

Member discussion