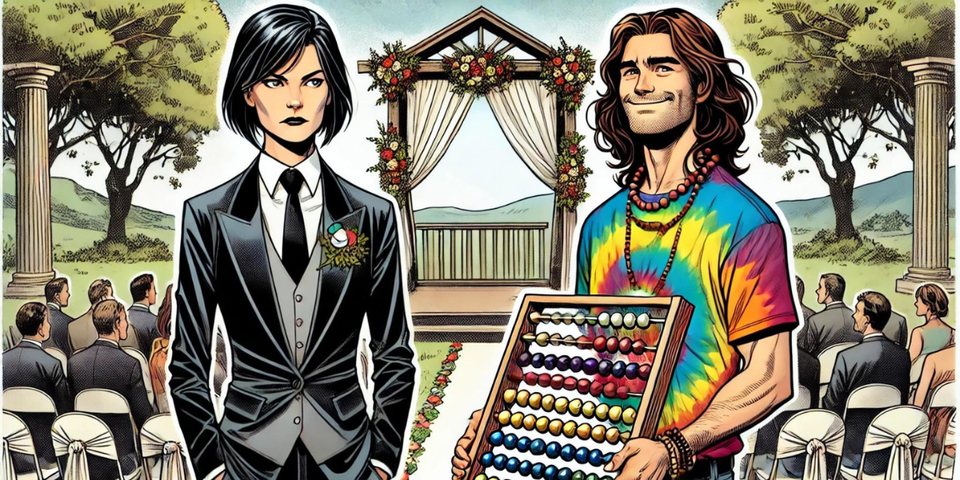

The unhappy marriage of climate and financial disclosures

This is a free-to-view edition of Unpacking Climate Risk. Become a paying subscriber today to get articles sent direct to your inbox three times a week.

Pity the bean counters. They’re not having an easy time incorporating climate-related risks in financial statements – and they’re getting whacked left and right for this perceived shortcoming.

The International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) is trying to help. Just this week, they published a series of “illustrative examples” to try and clear up the reporting of climate-related uncertainties in financial statements. It’s the latest in a series of efforts to solve accountants’ problems reconciling climate and financial information – efforts that only seem to spawn further questions and fresh ambiguities.

Back in March 2023, the global standard-setter started a work plan to “explore targeted actions to improve the reporting of the effects of climate-related risks” in financial statements. This apparently followed “strong demand” from accountants and other stakeholders, who were worried that climate risk information in companies’ financial statements was either “insufficient” or “inconsistent” with data provided outside these statements – like in their climate/sustainability reports.

Wind the clock further back to November 2019, and there’s IASB member Nick Anderson trying to explain how and when climate issues should be reflected in financial statements. Clearly, the IASB has been working on answering accountants’ questions for at least half a decade now, and is seemingly having very little success. Is it possible reconciling climate disclosures and financial statements is simply too tall a task?

It’s worth taking a step back here to consider where these problems may have started, and why unease over the inclusion of climate risk in financial statements persists. Such an examination inevitably highlights the smoldering tension between climate/sustainability and financial disclosures.

Let’s get into it. The push for companies’ to produce climate/sustainability disclosures (sometimes called “non-financial disclosures”, because they go beyond pure financial statements) goes back decades. Early efforts focused on sustainability issues like pollution and environmental damage, before evolving with the rise of the ESG to cover social and governance issues, too. The 2015 Paris Climate Agreement marked an important turning point. The pact shifted focus to how countries, companies, and financial institutions could support efforts to limit global warming. It also contributed to the launch of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), the acronym that has haunted my writing career for half a decade now.

The inclusion of “financial” in the title of this task force was significant. This was the group that blurred the lines between non-financial and financial information in a way that I’d argue has led to accountants’ current plight. Indeed, this blurring was a function of the TCFD’s very real success. The group powered the mass adoption of climate disclosures by companies and financial institutions, winning over 5,000 public supporters since 2017.

More consequentially, the TCFD’s recommendations were transposed into disclosure regulations in many countries, giving climate reporting a whole new level of institutional legitimacy. I’d argue the high-water mark of this transformation occurred in 2021, when the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) Foundation (which oversees the IASB) announced it would set up an International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) to produce sustainability disclosure requirements that would borrow heavily from – you guessed it – the TCFD.

So we have a situation where a climate/sustainability disclosure body lives under the same roof as the world’s premier accounting standards body. On the one hand, the IFRS’ imprimatur endowed the ISSB with the heft necessary to power broad take-up of its standards. On the other hand, this (unsurprisingly) led to questions as to how climate/sustainability disclosures should interact with financial reporting – questions that, as this week’s publication of illustrative examples show, have yet to be adequately addressed.

Undoubtedly, the framing of TCFD-aligned reports as climate-related financial disclosures forced preparers to wrestle with the extent to which these reports should compliment what was featured in their financial statements.

Climate advocacy groups piled on the pressure, too. The Carbon Tracker Initiative has surveyed the disclosures of high-emitting companies for four years now, and has consistently found, well, inconsistencies between companies’ climate-related disclosures and financial statements. In this year’s report, the group said that none of the 140 companies analyzed “provided a fully consistent climate narrative across its financial statements and other reporting.” Moreover, 60% of firms failed to “provide meaningful information about whether, and how, climate risk and the energy transition impact the financial statements, or the audits thereof, today.”

What does the analysis tell us? You could look at it a number of ways. Is it the case that companies are willfully neglecting climate-related factors in their financial statements? Have most companies put up firewalls between climate and financial reporting, believing them to be separate disciplines? Or is it that companies want to marry their climate and financial reporting – but find it too darn complicated?

A fact that supports all three of these interpretations is that companies are terrified of misreporting financial-related data to the public. As Bloomberg’s Matt Levine likes to say, ‘Everything is Securities Fraud’. If you’re a public company, and you put something in your financial disclosures (or leave something out) about a certain risk or financial factor, and then a bad thing happens caused by that risk/factor, you’ll probably be sued for producing “misleading” disclosures. Being sued is no fun. Hence why companies are very cagey about what they put in their public reports, and tend to use boilerplate statements about issues like climate that don’t box them into a corner.

The Carbon Tracker Initiative itself found that where climate matters were referenced in financial statements and audit reports, “frequently these were generic comments about the existence of the energy transition and/or support for the goals of the Paris Agreement; some repeated the risk and target discussions from their other reporting.” This is evidence of a highly cautious approach to climate-related financial disclosure. But it doesn’t point towards one or another of the three interpretations.

Why I tend toward the “it’s too darn complicated” explainer is that clearly many companies are trying to reconcile climate and financial reporting. Indeed, in the UK, European Union, Singapore, and other jurisdictions, they simply have to – thanks to regulation. If companies generally didn’t care about this, I doubt the IASB would have felt the need to establish a dedicated work plan in 2023. Of course, the very existence of the ISSB, and confusion about how IASB and ISSB standards interact, probably played a role, too.

Why is it too complicated, though? I detect a common thread that runs through the IASB’s recent publications on climate-related financial reporting: materiality. A key challenge appears to be determining whether a climate-related risk factor should be disclosed – even when it is deemed not to affect a given financial line item.

In Anderson’s 2019 article, he cited the hypothetical example of a company in an industry likely subject to climate-related risks (think a power company in the utility industry). This company may, following financial analysis, determine that it doesn’t need to factor climate risk into its assumptions regarding asset impairment. One may think, then, that climate risk wouldn’t have to be referenced in the impairment disclosure. But as Anderson explains:

“...taking into account investor comments on the importance of climate-related risks to their investment decisions and reasonable expectations that the recoverable amount of the company’s assets could be affected by such risks, when applying the Practice Statement, the company may conclude that it needs to disclose information that explains clearly why the carrying amounts of its assets are not exposed to climate-related risks. Such an explanation may provide material information to investors even though the carrying amounts in the financial statements are not exposed to those risks.”

What this says to me is that investor belief that climate risk is important to an industry leads to a presumption that climate has to be a factor in a firm’s financial accounting. In some cases companies may have to bow to this belief by talking about climate factors even when they don’t matter to their financials.

Knowing where to draw the line is what’s proving tricky. Five years on from Anderson’s article, guess what two of the eight illustrative examples concern? Materiality. One considers an example where a company discloses that its climate transition plan has no effect on its financial position and financial performance and explains why; another where a company determines its marginal greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions has no effect on its financial performance and doesn’t explain why.

These aren’t niche examples. After all, loads of companies are producing climate transition plans and are reporting their GHG emissions. I think what’s going on here is that the fanfare around transition plans and climate data, pumped up by the TCFD, certain regulatory bodies, and the ISSB, has created an environment where it doesn’t seem feasible to investors that climate doesn’t have an impact on companies’ financials. The vibe is: “these climate disclosures are vital and necessary, and so they must affect every aspect of a companies’ financials.”

The thing is, in lots of cases this won’t actually be true. A transition plan that doesn’t force a company to overhaul its capital expenditure plan, change its product mix, or shutter existing physical assets very well may not be financially relevant, no matter how impressive the standalone report trumpeting the plan is. In the first example in the IASB document, the hypothetical company (a carbon-intensive manufacturer) has facilities that “are nearly fully depreciated” and cash-generating units with recoverable amounts that exceed their carrying value – factors that inform the conclusion that the transition plan is not financially material.

It’s an uncomfortable place to end up, I realize. On the surface it does seem odd that climate risks, well-documented in companies’ own climate/sustainability reports, often won’t be financially material. But this doesn’t mean it is wrong.

A desire to tie climate and financial reporting more closely together has given rise to a strong belief that the former must inform the latter. The truth is, in lots of cases it’s marriage that just doesn’t make sense.

Member discussion