Weather shocks and the “adaptation put”

This is a free-to-view edition of Unpacking Climate Risk. Become a paying subscriber today to get articles sent direct to your inbox three times a week. For a limited time, annual subscriptions are 20% off!

The put option is a beautiful concept, a feat of financial engineering that speaks to broader truths about human nature and economic behavior.

To the Robinhood-toting day trader, a put option is a contract granting the holder the right, but not the obligation, to sell a financial security at a set price, on or before a specified date. It’s a product that tugs at our cognitive bias toward loss aversion. In general, we hate losing more than we love winning.

Put option mechanics apply beyond the tidy contracts traded on smartphone apps, however. Companies, institutions – even whole countries – use puts to backstop losses, financial or otherwise. For example, the “Greenspan Put” was shorthand for how Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan (who served 1987-2006) would appear to bail out stock investors at times of market turbulence by cutting short-term interest rates.

Similarly, I wonder whether an “adaptation put” could act as a floor on economic and financial losses incurred in the wake of severe weather shocks – which are being made more destructive and frequent because of climate change.

What sparked this line of inquiry was a new paper out of the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) on how “acute physical impacts from climate change” – in other words, weather shocks – could affect monetary policy. Now I’ve bashed the NGFS plenty in my time, mainly because it talks more about how climate change could impact central banks rather than how central banks could impact climate change. Still, their papers are typically well-researched (though Tony may disagree!), and provide a useful snapshot of the prevailing literature on various climate-related financial issues.

This one’s a corker because, like a Rorschach test, it can be interpreted in many different ways depending on your priors. For example, the paper repeatedly cites Swiss Re’s finding that weather shocks caused $275bn in damages in 2022, more than double the amount suffered in the early 2000s in real terms.

What could be heralded as evidence of climate change’s monstrous financial impacts to some can be easily discounted by others – especially when you factor in Swiss Re’s additional findings. For one, the insured loss rate tracks with a 5-7% annual growth trend in place since 1992, and for another, the “main driver of rising losses” are the buildup of valuable assets, like real estate, in disaster-prone regions (we’re looking at you, Florida).

Yours truly read the paper and wondered whether the conclusion one should draw about weather shocks is that they are likely to encourage put-like dynamics at a societal level that would actually support indicators of economic health and bolster asset prices (similar to Tony’s argument earlier this week).

Let me provide an example.

In one section describing how weather shocks could affect economic demand, the NGFS says they could result in lower aggregate spending which would “drag on economic activity.” This is because household wealth and income expectations would change in response to devastating floods, fires, storms and the like – and knock consumer confidence, too.

However, surely aggregate spending increases in the wake of disasters as governments pour relief funds into affected areas, insurers pay out claims, and donations flood in? Hurricane Ian, which tore through Florida in 2022, caused around $118bn in damages. It was a horrific tragedy.

But what about the impact on spending? A year on from the storm, the federal government had spent nearly $9bn on affected areas, including grants to 386,000 households, loss of income support to affected workers, and funding for temporary jobs. The state of Florida pumped in additional tens of millions of dollars, including huge chunks of change to rebuild and reinforce infrastructure over time. And the insurance industry paid out billions too – though not as much as some policyholders say is fair.

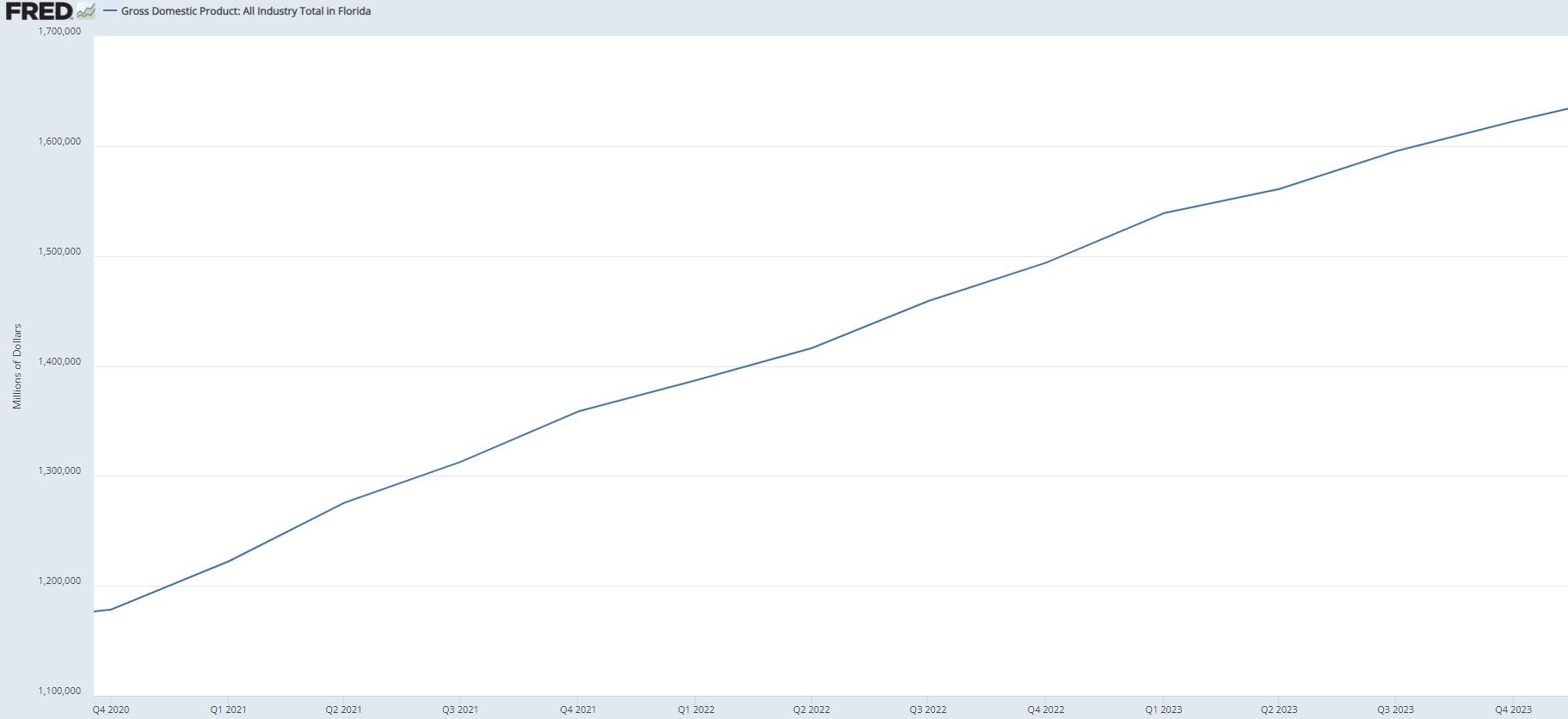

This all goes some way to explaining why Florida’s GDP didn’t dip in the aftermath of the storm, though the rate of growth did slow somewhat. Indeed, the NGFS cites research saying that while GDP growth rates decline by around 0.5 percentage points in the year following a shock, over time the growth rate recovers. While it’s unclear whether the economy returns to its pre-shock path or not, what doesn’t seem to happen is spending contracts.

Gross Domestic Product of Florida: All Industry Total

Now of course lurking beneath the smooth GDP growth trendline are tens of thousands of low-income Floridians who are still struggling to make ends meet, earning less – and spending less – than they did before Ian. But aggregate spending is what matters here. When the biggest spenders of all open their wallets in the wake of a disaster – in this case, the federal government – aggregate spending is likely to rise. In the case of Hurricane Ian, Florida was the put buyer, and the US taxpayer the put writer.

But this kind of disaster relief spending isn’t the same thing as the “adaptation put” I was rambling about earlier. What I mean by the adaptation put is the spending unleashed in advance of weather shocks to better adapt to their impacts. My thinking is that this spending puts a limit on the losses incurred by extreme weather events when they hit.

In the NGFS paper, this dynamic is couched in the language of “resilience thresholds.” This is the sum of a country’s wealth, fiscal capacity, insurance mechanisms, and other resources that enables them to handle and bounce back from weather shocks. Events of an intensity and magnitude below this threshold lead to reduced impacts on human and economic activity than events above this threshold. Naturally, the richer, better resourced, and better prepared – in other words, the more adapted – a country is, the higher its resilience threshold and the worse a weather shock has to be to inflict meaningful damage.

What’s important to recognize here is that a country’s resilience threshold can rise if it spends on strengthening infrastructure, improving building safety, and installing things like advanced flood defenses and storm shelters. At the individual level, household resilience thresholds can be raised by splashing out on advanced air conditioning (to deal with heat waves), storm shutters (for hurricanes) and vegetation management (for wildfires), among other things.

In options speak, all this activity raises the “strike price” of the put option: the level below the current price of assets at which losses will be avoided. The higher the resilience threshold, the lower the losses suffered following (most) severe weather events.

Of course, put options don’t come for free. Someone has to pay for the climate-proofing of infrastructure, property, and supply chains. My feeling is that governments will have to serve as the ultimate put writers, not only because they have the resources and wherewithal to write a comprehensive adaptation put, but because political and social pressures will require them to.

So, does this mean the private sector doesn’t have to worry about weather shocks affecting their financial performance? Can they go along their merry way secure in the knowledge of the never-expiring adaptation put? Only if they’re willing to ignore the knock-on effects. Because in order to write this put, governments have to invest resources that could otherwise go toward research and development, education, and all the other things that fuel GDP growth. The increased public spending could also put upward pressure on inflation. Think Florida coastal homes are expensive now? Imagine how much pricier they’ll get once effective flood defenses are put in place.

True, adaptation investment can and should also promote innovation, if done right, and should be additive to GDP. Yet what’s true for the RobinHood day trader is true for the weather-plagued country: to protect from losses, you have to give up some potential upside.

Member discussion