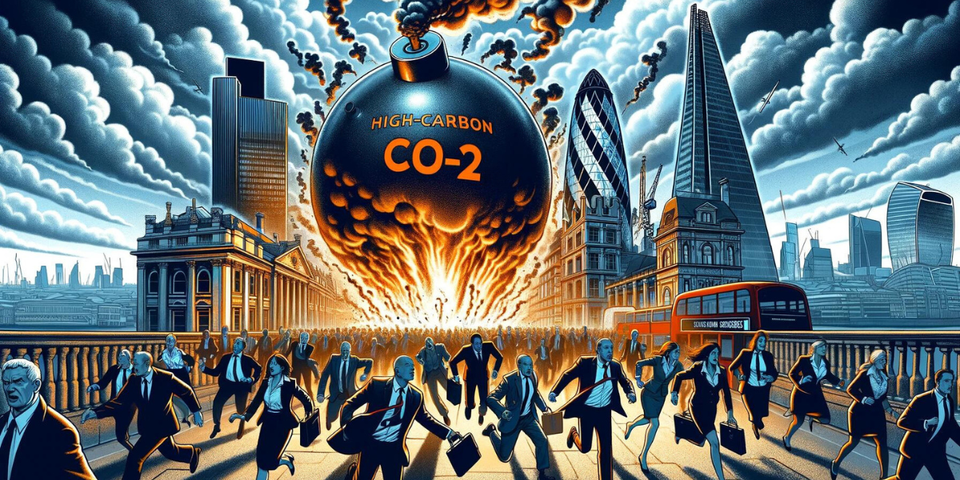

What if emissions aren’t a good proxy for transition risk?

This article has been made free-to-view. Like what you read? Then consider buying us a coffee here👇

Nearly ten years on from the founding of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), climate risk reporting is still a contentious topic.

At least, that’s the impression received from the responses to the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision’s (BCBS) consultation on a climate-related financial risk disclosure framework, which closed earlier this month.

As is standard for proposals issued by the global panel of banking regulators – so often caught in the middle of opposing ideological extremes – climate hawks and doves alike were unhappy with the draft.

On the surface, it’s hard to see why. The proposal amounts to a fairly tame request that banks produce more data on their portfolios’ exposure to climate physical and transition risks, and publicize said data in standardized templates.

In a post-TCFD world, where climate risk disclosure rules are already in place (or in the process of being implemented) in Europe, the UK, Hong Kong, Singapore and even the US (lawsuits pending), the BCBS effort shouldn’t come as a surprise. Indeed, European banks are conforming with many of the requirements already through the introduction of ESG disclosure rules ushered in by local regulators in 2022.

Of course, for climate hawks the “fairly tame” nature of the proposal is the problem. James Vaccaro, one of the savviest climate hawks, took umbrage at the proposal’s failure to force lenders to drill through layers of financial intermediation and report the ‘true’ amount of emissions they facilitate. In his model, the quantity of emissions a bank finances is a fair proxy for its transition risk exposure, so failing to make institutions report the climate pollution associated with the loans they make to other financial institutions (which then use this credit to bankroll high carbon activities) is a dangerous omission. It leads to an underestimation of transition risk in the “traditional” banking system and a build up of it in the under-regulated “shadow banking” world.

Yours truly has written about this before, and I remain convinced that in a financial system characterized by complex ties between a highly regulated banking ecosystem and network of footloose non-bank financial intermediaries, it’s vital that supervisors pay attention to the latter.

And just recently, we’ve heard reports of cunning financiers cooking up complex carbon risk transfer trades that could shift emissions off banks’ books, thereby concealing their true exposure to climate-polluting assets and making Vaccaro’s fears a reality.

But look, as much as I want to bash the bank lobby’s more tenuous complaints about the BCBS proposal, in the interests of being intellectually honest I have to say I’m increasingly doubtful that financed emissions – reported in isolation and out of context – make for a decent proxy of climate transition-related financial risk.

As long-time readers know, I’m of the view that climate risk is a systemic risk, and therefore that more emissions equals more danger to human, economic, and financial systems. This danger will ultimately become existential if we do not cut cut emissions and adapt to climate shocks over the coming decades.

But this does not mean that financial risks are going to increase in lockstep with atmospheric carbon levels. Certain high-carbon assets, like coal-fired power plants, in developing countries may be safe financial bets up to 2040, and perhaps beyond, because those countries’ decarbonization pathways have a place for coal in their energy mix.

On the flipside, in developed countries whole sectors could see their creditworthiness jerk up and down in response to policy changes that aren’t directly tied to emissions volumes. I’m particularly interested to see how the perceived riskiness of US auto companies moves around over the coming months in response to President Biden’s regulation of tailpipe emissions.

Indeed, it seems to me that climate-related financial risk in the short term is manifesting largely through policy rather than technology or market regime shifts (climate litigation too is clearly having an impact on select companies, but by nature this risk is idiosyncratic). Orthodox climate scenarios express this policy risk through a carbon pricing proxy, buttressing the idea that the higher a bank’s financed emissions, the greater its transition risk exposure.

This just isn’t credible. For one, the ‘price of carbon’ – set via actual compliance carbon markets/taxation regimes or indirect regulatory costs on high-emitting activities – is and will continue to whipsaw in response to political and policy changes. It won’t simply climb up and to the right over time. For another, this price will vary wildly from sector to sector and geography to geography. We’re getting used to the idea that climate physical risk is spatially and temporally dependent. We should get similarly comfortable with the idea that transition risk is, too.

These characteristics of transition risk mean that the link between financed emissions and financial risk metrics, like probability of default, are poorly correlated, at least for now. Of course, high-emitting companies are gambling that their pollution will continue to go largely unpunished in the near future. But while the sudden imposition of a direct carbon tax can’t be ruled out in key jurisdictions, it’s likely companies will adapt, either by passing costs downstream or moving operations to more permissive countries.

Furthermore, financed emissions are a backward-looking indicator, whereas meaningful risk metrics should be forward-looking. As the Institute of International Finance (IIF) said in their response to the BCBS consultation: “in some industries, a borrower with a higher starting level of GHG emissions and a credible transition plan may be less exposed to transition risk over the medium-to-long term than a borrower with lower starting GHG emissions and no transition plan.”

What’s the bottom line? Well, if emissions aren’t a decent proxy for transition risk, then reporting them under a framework that is supposed to be narrowly focused on banks’ capital adequacy and actual risk exposure is problematic.

To be clear, I’m completely in favor of forcing financial companies (indeed all companies) to disclose the emissions they’re responsible for. This data is useful to policymakers crafting transition policies, and for investors wanting to manage carbon exposures in line with their stewardship and sustainability commitments. I also think the data can supplement other transition risk metrics, like climate value-at-risk and temperature alignment.

But we need to be honest that on their own, financed emissions numbers can’t tell us much about an institution’s financial risk. It’s not the amount of emissions that matter in this context. It’s where they’re produced, and over what time horizon they’ll continue to be pumped into the atmosphere. Without this kind of supplemental data, forcing financed emissions numbers into pure play risk disclosures doesn’t make sense.

Member discussion